[Wait and see explores the world of João César Monteiro, a director already mentioned in Nous voici encore seuls and Home Sweet Home. The author’s understanding of his work was deeply changed by the familiarity with Malick’s universe. Here are exposed the main conclusions. Knowledge of Monteiro’s films is necessary to follow the arguments. Malick is only indirectly related to this post, contrary to what happens in the rest of the blog. So, if what interests the reader is only Monteiro, it is not useless to read the following before The Imaginary Family of Terrence Malick, as all other posts announce.]

To Terrence Malick. After all, without his films the following lines would have never been written.

|

| The camera as a gun: a classic. |

Mimi: I trust you. I don’t know why, but you inspire confidence in me.

John of God: Me? You have nothing to fear from me, but if I were you, I wouldn’t be so trusting. There are lots of rogues around.

(Recollections from the Yellow House, 1989)

Portugal, beginning of 1975. Just one year before a military coup ended with 40 years of conservative dictatorship in Portugal and its war against the independence movements of the African colonies. As the oldest and most organized political actor in action, the Communist Party was assuming the leadership of the revolutionary process. Fearing that the Carnation Revolution would develop into a pro-Soviet communist regime – and so the Portuguese colonies, with short-term perspectives of independence – the USA made their force visible through NATO’s maneuvers in Lisbon. The American intervention in Chile was recent. The climate was tense in the capital, .

Monteiro’s What Shall I Do With This Sword? was born from the desire to pick a camera and simply go to the streets in search for the revolution. The revolution of the people, not of politicians (not a single one appears in the film). The protests against NATO’s silent threat happened to be its conducting thread. The making of the film was fast. In the summer of 1975, during the peak of political tension in Portugal, the film was exhibited in the public television.

It is more than the famous association of the American warship, whose men are interviewed, with Nosferatu’s (note the phonetic resemblance in Portuguese between NATO and Nosferatu; extracts of Murnau’s film are paralleled with the arrival of the USS Saratoga). It is the pretext to build a fresco of the working people, from agricultural laborers to a prostitute, in a moment Portugal was in risk of changing from colonizer to colony.

|

| “Reporter: But… you never had a profession? John of God: Put artiste-saltimbanque or nothing.” (The Hips of J. W.) One of the unexpected, rather surreal moments of the film, is the burlesque childbirth filmed by a clown. This is hard not to take as a metaphor of the film, Monteiro, the man with the movie camera, filming the new-born society. The scene would be somehow reinvented in his final Come and Go (2003). |

What Shall I Do With This Sword? A film-question. A question the workers should put to themselves: what shall I do with freedom? More precisely a question of the filmmakers. And in particular a question made by Monteiro to himself: now that I am free to film, what shall I do with cinema? Symbolically, the students from the former colonies give an answer (with reference to Amílcar Cabral). Cultural war. Only the societies which preserve their culture can mobilize, organize and fight against foreign domination.

“Io sono una forza del Passato” (“I am a force of/from the Past.”), wrote Pasolini in one of his most beautiful poems. Although cosmopolitan, Monteiro’s oeuvre, exploring the richness and idiosyncrasies of Portuguese language, developing an intense historical and anthropological voyage through Portugal, seems to develop that way, particularly in Paths (1977) and Silvestre (1982), just to mention the features, perambulations in the world of folk-tales and legends. But revolutionary enthusiasm must be restrained fast. Monteiro’s relation with his own country, his dear mother-land, was problematic, to say the least. In his decisive He Goes Long Barefoot That Waits For Dead Man’s Shoes (from 1971), a “cinematographic proverb”, it is said “an ass from where one can’t get out.” The diagnostic was not better in his latter films.

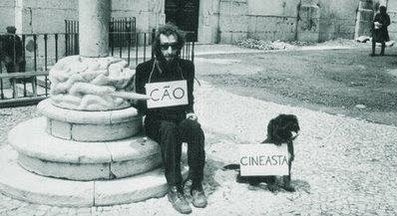

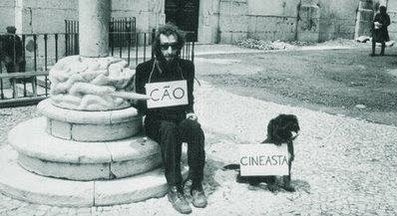

|

| Dog (left), cineaste (right). |

Monteiro’s sword was indeed the camera, his kino-eye. So it says the cannon pointed to the enemy, the USS Saratoga. And it is indeed a cannon from a distant past, one capable of embodying centuries of Portuguese culture (“It is so old. Older than anything in the USA”, comment the Americans in the film). But irony – self-irony – is not far from this shot. We feel the clown camera-man there. Monteiro resists the invader (or metaphorises the Portuguese people’s resistance) with a weapon in total contrast with the immense artillery of the Saratoga, whose threat hoovers over the city. A remarkable phallus that points to its target, but old and impotent. A picturesque detail of the décor of Saint George’s castle, a central monument of Portuguese nationalism converted into a belvedere by the former regime.

|

| The spot in 1955 by Cartier-Bresson. |

An eye perverse enough for Monteiro will recognize here the distinctive mark of his “Lusitanian comedy” (as Recollections of the Yellow House presents itself, a subversion of the Portuguese comedies popular in the former regime), more than of cinéma militant.

Let us look further. The female incarnation of the founder of the nation suggests the idea of a muse and a personification of Monteiro’s cinema, something he would explore in the future. In an experimental and revolutionary film, the pompous iconographic choice, so much in the tradition of the former regime (the founder of Portugal, the great crusader who fought for independence), is at least suspect.

|

| The warrior, of course, also personifies Portugal. Important is the preference for the image of motherland (matria) instead of fatherland (patria). In Paths, Silvestre and God’s Comedy female warriors would appear again. The sword reappears in The Hips of J.W. Bellow, the statue of the founder of the nation in the castle. |

Anti-Americanism, although diverse, was one of the continuities between the dictatorship and (theoretically) Monteiro’s left, close or member of the Communist Party. So: ambiguities of the revolution? Of Monteiro’s ideology? The ghosts of the old order haunting the new Portugal? We hear the Wedding March when then a newly married couple is interviewed. If we wanted to provoke this fan of Past and Present (1972) we would ask him if he, like the woman of Oliveira’s film with her dead husbands, was not beginning to fall in love for the former order. Ambiguous was also, after all, the title, took from one of Pessoa’s most nationalistic, messianic and esoteric works, his Message, to baptize a revolutionary film. Did Monteiro identify himself with its “message”? He did a later reference to this very literary work, to its final verse “The Hour has come!”, in the end of the short Consersa Acabada (1990), as the camera close-ups the generous breast of an aspiring actress. Absolute derision.

“You pay a drink me?” The sculptural figure of the warrior has its counterpoint in the prostitute. A testimony filmed à la Godard. Generous measures, Fellinian appearance. Stories in which the humor of the later films shines already. A kind of Mother-Lisbon, but without the pathos of the Roman. Decadent, entertaining Americans, priests, perverts. She aspires to change of way of living. The director seems skeptical. He inserts in the middle of the interview a street chat where a man says we would not bother if his wife prostitute herself. As long he had some daily easy money...

It is the first appearance of the whore from whom the director would farewell on the steps of São Bento in Come and Go (2003), his last film.

Monteiro’s whore, the public woman, the republic. Life. Indeed, in Portuguese and Italian a prostitute is sometimes called a woman “da vida”/ “di vita”. As the song of the streets animating the round dance of The Last Dive (1992), it is not mine nor thine nor anybody else’s. She punctuates the director’s films, from Mimi, the victim of Recollections of the Yellow House (1989), to the dictatorial Judite, the businesswoman integrated in the new social order of Comedy of God (1995).

The whore – that ultimate symbol of the marvelous deeps of the sea of life – is the pair for Monteiro’s cannon. Among them is celebrated the tumultuous marriage from which this art is born. “We expect the best.” Said the bride and groom in the comic photo session in the castle.

|

| “I’d put a match to it and set the rotten straw mattress on fire [traveling over the city, toll of the bells], and then I’d joyfully dance over the flames while listening to them ''crack, crack'' popping like chestnuts in the fire.” (Recollections of the Yellow House) Fire is also very important in Monteiro (he speaks of “my fire” in God’s Comedy). Since his early films. |

Significantly, Recollections of the Yellow House begins with a long shot of the city (the castle is up there) from a moving boat, reversing the perspective of What Shall I Do With This Sword? Monteiro invites us to search the meaning of the Trilogy of God (and of his later work in general) in connection with his revolutionary film. Accepting the proposition would be to illuminate What Shall... with the trilogy’s light – impossible or too obscure in 1975 – and vice-versa.

Now the vampire arriving town is another. He is Monteiro himself (he will identify with Nosferatu and Knock from this film on). Why? In 15 years the Americans absorbed Portugal in their empire. The country was integrated in the European Economic Community. The revolution is dead. A new, unscrupulous as usual, political and economic order rules the country. Is it because the people is lost for the enemy that the perspective is reversed? As he come to reconquer the new American (or/and German?) colony and expel its representatives? Both the adversaries’ real and cultural weapons are invulnerable to our creator’s efforts, as he well knows. And he has not come back with a revolution to sell. That is not the idea at all.

“My politic is the gelato.” The truth is that the gelati (Italian recipe, distinctive from the American “ice cream”) did not enter Monteiro’s film in the Trilogy of God. They entered in What Shall..., in one of the exotic stories of the prostitute. She recalls two special clients sharing the same “sickness”, a priest whose procedures unutilized her for weeks and a man who bought a gelato in the way to the hotel. Curious why he did not ate it right away, she asked him. “Wait and see,” answered the gentleman. At this point of the edifying story the prostitute points and laughs at someone out of the frame. The man had in mind to taste the gelato somewhere in the lower regions... I did not like this kind of intercourse, she concludes.

The sordid tale is more than it seems. It involves two highly symbolic presences in Monteiro’s oeuvre, the gelati and the prostitute, the film (the cannon) and mother-land. The conclusion is that the latter films of Monteiro assume themselves as the answer to 1975’s decisive question. What Shall I Do With This Sword? “Wait and see.”

|

| The cannon pointed to its new target. (God’s Comedy) |

Vampirized by the fin de siècle’s cynical pessimism and perversion, the revolutionary documentary sounds quite different. It was never exempt from irony and ambiguity, far from that. But now the murals with the graffiti (“workers of the world unite”) seem pre-historic relics and the ridiculous of some characters or the terrible articulation of their ideas imposes to the grotesque. Never so much like with the old communist trying to transform into heroism his life of sad submission, filmed for several minutes in one of the cruelest shots of Monteiro. Applauded by the audience to each bêtise, he enjoys his moment of authority and prolongs his speech endlessly: “put your eyes on me, put them on no one else.” It is difficult to find a more derisory image of any revolution.

Monteiro said himself that a film is the “foreshadow of our own history, the silent projection of our own phantasms.” (He Goes Long Barefoot That Waits For Dead Man’s Shoes) From the light of the future we can say that something was infiltrating the town besides the American boogie man. The innocence Monteiro might once possessed was already raped by then. It is a good idea to read the poem which baptized the 1975 film, (John of) God’s divine joke:

All beginning’s involuntary.

God’s the agent.

The hero observes himself,

Multiple and unaware.

Your gaze drops

To the sword found in your hands.

"What shall I do with this sword?"

You raised it. And it was done.

“We don’t search Truth. We search our Ariadne.” The call of life, desire, its perfume, the call of love. That sweet poison. Ferdinando, his boss in Recollections…, shows him two pictures, one of starving children and other of a private dinner of some important political actors to ask him a populist article emphasizing the contrast between the terrible poverty of ones and the decadent orgy of others. After some ironic comments, the conversation ends with Monteiro offering him an obscene photo with the friendly words: “Take this one and shove it up the ass.” Got the idea? Ferdinando’s character was played by a great cinephile, long friend and supporter of Monteiro. Choosing Jean Douchet to play the gelati critic in God’s Comedy («…c’est de la merde. »), was the same kind of joke.

|

| “There is only one Mother of God.” (Recollections...) We first see John of God in the empty church. The mother and the child, an important theme in Monteiro. |

“You see, she said, I am GOD.” (« Tu vois, dit-elle, je suis DIEU. », Madame Edwarda). John of God is nothing but John of the Cunt. It would be terrible to obscure the seriousness of the matter. As Professor Salazar told to his governess, “we aren’t here to amuse ourselves.” (Monteiro to the TV reporter, The Hips of J.W.) What conducts this search, this voyage towards the deeps, is the sacred. And believe me he had read Bataille.

|

| Paths ends with one of the most beautiful shots. At a first look (but maybe only that), the performance of a traditional fertility rite, a baptism in ventris, is a significant political commentary. The woman (vulva) is associated with the earth (with Portugal, somehow; see the previous shot), becomes a kind of landscape. She opens her legs, the man drops the water and says the formulas. |

What is John of God’s door to it? His insistence in the vulva – l’origine du monde – in kissing, licking, smelling it (Barreiros’ song) is not to be neglected as a dirty cliché. The same for the burning bush whose vision causes him near epileptic convulsions. His collection of pubic hairs might just express the desire to make a gigantic, cosmic cunt, one condensing all the bitter-sweet perfume of life. His perfume of perfumes, his final glorious gelato. In John of God’s first encounter with a thread of Ariadne we recognize a birth of Venus. The pubic hair is in the middle of the foam of the girl’s bath, drank by the adorer.

|

| So much the devotion to the Holy Wound was eroticized that it inspired religious parody: a badge with phalluses carrying a vulva in procession (Bruges, fourteenth century). Monteiro finds a place in this tradition, in this religion. Have in mind that the association with a priest goes back to the 1975 movie. |

From Recollections... the cannon/phallus is now positioned towards the city, a ruined decayed world where the poet kills himself and resurrects as Stroheim, Nosferatu... Life and its call in Monteiro are strange to good intentions and high ideals. The artist is alone with his low passions and becomes a vampire searching for nourishment in the city. The ties between the artist and the people – any concept of people – where cut off, not only with military, political, economic and religious powers.

|

| Identification with Pessoa – “persona, persona non grata” – is obvious in Conversa Acabada, one of the finest examples of Monteiro’s specularity. The concept of heteronym is commonly proposed as one to understand this director’s alter-egos. |

Monteiro’s He Goes Long Barefoot... introduces us Lívio, his alter-ego, in a conversation with a friend who tells it was time for him to stop acting like a fool and Russian novelist. It is an allusion to a poem by Campos, Pessoa’s most famous heteronym:

We crossed paths on a downtown Lisbon street, and he came to me

That shabby man, a beggar by profession, you could see it in his face.

He felt drawn to me and I to him;

And in a generous, reciprocal gesture, overflowing, I gave him everything I had

(Except, naturally, what was in the pocket where I keep more money:

I’m neither a fool nor a Russian novelist, not conscientiously, anyway,

And romanticism is fine, but you’ve got to take it slowly...)

I feel sympathy for people like him,

Especially when they don’t deserve sympathy.

Yes, I’m too a beggar and a bum,

And likewise through no one’s fault but my own.

To be a beggar and a bum doesn’t mean you’re a beggar and a bum:

It means you’re unconnected to the social ladder,

It means you’re unadaptable to life’s norms,

To life’s real or sentimental norms

It means you’re not a High Court judge, a nine to five employee, or a prostitute,

Not genuinely poor or an exploited worker,

Not sick with an incurable disease,

Not thirsty for justice, or a cavalry officer,

Not, in short, within any of those social categories depicted by novelists

Who pour themselves out on paper because they have good reasons for shedding tears

And who rebel against society because their good reasons make them think they’re rebels.

No: anything but having good reasons!

Anything but caring about humanity!

Anything but succumbing to humanitarian feelings!

What’s good a feeling if there’s a external reason for it?

Yes, being a beggar and a bum like me

Isn’t just being a beggar and a bum, which is commonplace;

It’s being a bum by virtue of being isolated in your soul,

It’s being a beggar because you have to beg the days to go by and leave you alone.

All the rest is stupid, like Dostoyevsky or Gorky.

All the rest is going hungry or having no clothes.

And even if this happens, it happens to so many people

That it’s not worth the trouble to trouble over those it happens to.

I’m a beggar and a bum in the truest sense, namely the figurative sense,

And I’m wallowing in heartfelt compassion for myself.

Poor Álvaro de Campos!

So isolated in life! So depressed!

Poor guy, sunken in the armchair of his melancholy!

Poor guy, who this very day, with (genuine) tears in his eyes,

With a broad, liberal, Muscovite gesture,

Gave all he had – from the pocket where he had little –

To that poor man who wasn’t poor, who had professionally sad eyes.

Poor Álvaro de Campos, whom nobody cares about!

Poor Álvaro de Campos, who feels so sorry for himself!

Yes, the poor guy!

Poorer than many who are bums and bum around,

Who are beggars and beg,

Because the human soul is an abyss.

I should know. Poor guy!

How splendid to be able to rebel at rallies in my soul!

But I’m no fool!

And I don’t have the excuse of being socially concerned.

I have excuse at all: I am lucid.

Don’t try to persuade me otherwise: I am lucid.

I have said: I am lucid.

Don’t talk to me about aesthetics with a heart: I am lucid.

Shit! I’m lucid.

(Álvaro de Campos, transl. R. Zenith)

|

| The Last Dive (1992): “This night, sweet and silky, open themselves the little cunts of the most beautiful princesses.” Eloi guides Samuel through Lisbon. He gets two whores for him and gives Samuel his daughter. They go to a shabby hotel with the name of the Portuguese revolution. Portugal is not a battlefield anymore, it is a brothel. Whose? |

Not only lucid. Unwilling to live a life prescribed by society, to live the impostures of others, to be an actor of a second rate play. In this respect, The Last Dive, a 1992 film made for the TV, calls for special attention. Eloi, an ex-seaman, approaches a young man looking to the dark waters of the river. He has been watching him for some time, suspecting he was going to commit suicide (or maybe not):

Samuel: You’ve been here over two hours waiting for me to jump in?

Eloi: Two hours and twelve minutes, to be more precise.

Samuel: If I jumped in, would you get me out?

Eloi: With all due respect, no. I’d follow you. I can’t stand this shit anymore.

Samuel: As that is the state of mind, it’s the right time for our last dive. Shall we?

Eloi: No. First let’s go and get a few drinks down our throats. Heaven can wait.”

Monteiro’s political ambiguity – or shameless sincerity – is expressed by the way he represents himself as an opportunist both ante and post Carnation Revolution. Both with the widow of Admiral Saladas – “needed some big time money, to start something, don’t know how. A comical journey don’t know where or why” – and the people he was supposed to defend in 1975 against foreign dominion.

|

| The appearance with the cavalry uniform might not only allude to Stroheim (Don Juan, cinéaste maudit, social satire). Monteiro presents himself at the police station as a “leftist intellectual”, but his outfit and monocle seems to parody António de Spínola (although he had mention other figure, one from the radical left), who tried to lead a counter-revolution in Portugal: “To march towards São Bento!” To be understood in the relation with What Shall I Do With This Sword?, I believe: “You don’t fool around with the troop, boy!” (“Com a tropa não se brinca com a tropa, meu menino!”) The Portuguese expression is currently used for much more than the army. “Troop” can stand for any group, any collective entity. Monteiro was always and growingly disappointed with society. For him, western democracies were a fraud in which he was not willing to participate. He said often, in and out his films, that he was not democratic. How God could be such a thing, right? “We are not democratic.” (The Hips of J.W.) “Down with the tyranny of freedom! Death to freedom! Long live God!” (The Spousals of God) |

In the end of the journey the Eloi jumps but Samuel decides to live. He has met Esperança (Hope), Eloi’s daughter. They seem both Monteiro’s alter-egos. Eloi is somehow responsibility towards the others, towards Portugal, his sick wife, who makes his life a hell. She insults him endlessly, accusing him of being an obsessive whore-fucker.

Monteiro seems to think: Oh, that’s the way it is? Wait and see... Now, he, like the Americans and the priest (religious and liturgical parody are essential in the Trilogy of God), explores Portugal, the prostitute, to his own ends, to form his own empire. To become God. João de Deus, John of God. Retrospectively, it is even more ironic the insertion of the end of Madame Butterfly in What Shall I Do With This Sword? The revolution (the dreams of the republic, the prostitute) can die, but I (or my films), her son (childbirth scene), shall live. And that is the important, as for the rest… “Business is a ruthless business, my dear.”

|

| A US. Marine during some aquatic maneuvers. (God’s Comedy) The parodic mirror image of the Americans is staged in the second film of the Trilogy of God as a war against the immense “empire of the American ice cream”, an eccentric metaphor for the American mass culture, particularly Hollywood’s. Maybe more than antithetic, Monteiro and the USA are presented as competing powers. |

But ambivalence inhabits the name of the most famous persona of the cineaste. Reduced to “Deus” (God) it proclaims the omnipotence of the creator. We add “de” (of) and it confesses us all João’s (John’s, Jack’s) insignificance, just a poor “son of God.”

In more than one way, the art of João César Monteiro defines itself as an impasse. The question of folly is highly significant in this respect. John of God is also the saint of lunatics. To some extent Monteiro played the court’s fool role in the post-revolution Portugal and the fool is an instrument of power. His folly only strengths reason, order and the logic of representation. The worst thing possible: he is socially utile. The poet could not escape the bitterness of such a condition. A profound sterility, impotence and void imprison him in a ever more closed, somber and small tower. The extravagance of the erotic games disguises a melancholic carnival. (As a matter of fact, there is no such thing as a solitary carnival.) The gates of Recollections…, the gates of the mad-house, open themselves to another prison. Like with the old court fool, he is permitted everything because he matters nothing. He is both God and nobody: John of God. What is the conclusion? The poet and mother-land (that ass one can’t get out from) develop a relation which seems at times a dead-end: “I stuck my finger in her asshole and we stayed like that.”

|

| “"We shall see what news this fool brings us", the King said. "It is you who is the fool, he is nothing", said the jester.” (Silvestre) Monteiro plays the king (the Cesar…), but insinuates a conversation with himself in the jester with his marotte. Note the color of the fool’s clothes are the Portuguese flag’s. Pure coincidence? |

***

Son: You are the most conservative and reactionary person I know. When your contradictions are exposed they’ll raise a laugh, but I must admit you fooled them all and so well you even fooled yourself.

Father: “Voici le temps des assassins”. I’m amazed.

Son: It’s not a recrimination. In your own way you are an artist. You take human beings and transform them into “objets d’art”. You despise everything around you that you don’t create yourself.

(Come and Go)

The prostitute is not only the ultimate symbol of life, a woman-cunt. It is also a classic instrument of male phantasies, illusions and frauds of love. Something about this was written in a past post on Vivre sa vie. It was said then that Malick compares his films to a brothel where the actors deliver their bodies to his phantasies, to that kind of spectrophila in which consists in great measure his filmic project. Is this side of the prostitute strange to Monteiro?

As it was remarked, John of God’s character is somehow born in He Goes Long Barefoot That Waits For Dead Man’s Shoes. For some reason Lívio and John meet in the mental hospital in Recollections... (Lívio says he has been waiting for John all those years), a work beginning the same way, with the director’s voice. Alone again, he confesses himself, talking in the dark of the room. We have to go back to that rather disturbing “old film”, a fragmental, enigmatic story. It is the story of a failed love and of a failed life. In the end, abandoned by that girl who “gets pregnant through her ears and aborts through her eyes” (insinuation of the Virgin?), alone in the woods, Lívio is already a vagabond, and one who might be, as we are told by his love, deprived from reason.

This “cinematic proverb” starts with a projection of filmic material from shootings made in the 1960’s and aborted for financial reasons. The result is awkward. We are presented to the film by its double. More precisely, the director (the camera) watching its double in the editing room. A film we are never going to watch. Or is it the other way around? Well, to augment the strangeness, the actors are different, at least the ones interpreting the main characters, but the place where Lívio meets Mónica (curious name) is the same. It is like the author was Vertigo’s Scottie. Searching for a dead/disappeared woman and/or a dead film, searching in those few minutes of celluloid for the foreshadow of his own history, the silent projection of his phantasms to embrace them next. In the new film itself the idea of double exists. The scene where Lívio runs after the train in the station is repeated twice, the second in negative and without soundtrack.

|

| The girl seen in the 60’s segment was no ordinary actress. Monteiro was in love with her when she left him and the country. It was really an amour fou: he was so devastated that ended in a psychiatric hospital for some time (like Scottie), an episode alluded in Recollections of the Yellow House when John of God meets Lívio. |

The double, the mirror, haunts all Monteiro’s work. Although there are plenty, we are talking of more than shots with mirrors or reflections. The preference for symmetrical compositions can also insinuate the mirror (left/right) or the repetition of scenes. But above all there is a concept of mirror structuring his filmic project. To the last shot. Only recently I understood: more than Duras, Oliveira, Cocteau, Tarkovsky, Hitchcock, Monteiro is the king – the Cesar – of mirrors in cinema.

Strange shot the one where she tells us about him. Unexpected. Enters the film like that cockroach falls from the ceiling. So symmetrical. So abstract. Surreal… a bite spooky. And so childish. Something of a fairy tale mirror. The queen’s mirror of Snow White. Yes… that is close to my impression. An apparition. A speaking oval mirror. Is the girl being reflected or is it a magic mirror? It is illusion, fraud (cinema…), but the camera seems positioned right in front and that only increases the awkwardness of it. It is an impossible, magic shot where the camera is invisible, like a vampire. A fraudulent shot. A shot where the world of mirrors is separated from that of men, or maybe exactly the contrary, like in the Fauna of Mirrors, read later by Monteiro. I wonder if among the many possibilities contained in the title of this last film is not an allusion to Cocteau: “Mirrors are the doors through which death comes and goes.” (« Les miroirs sont les portes par lesquelles la mort vient et va. », Orpheus) The mirror as the door.

The importance of this shot to the director is undeniable as it will metamorphose multiple times in his future work. It makes a rather tragic reference to the myths of Orpheus and Narcissus, the pair structuring Cocteau’s trilogy and, somehow, Scottie’s story, the story of a man who loses his love:

“And when he turned around, his loved one had vanished. As if the earth had swallowed her. He searched for her everywhere, incessantly chasing after the cherished image until, one day, exhausted and deprived, among other possessions, of his reason, he became aware that it was himself he was calling out for. Orpheus, having forgotten his chant, could do nothing but display the inaccuracy of his poor face.”

The film ends (inspired in Bergman/Truffaut?) with a long shot of the protagonist displaying his “poor face” (similar end in Snow White and, to some extent, in the mirror-eye of Come and Go; see also, at least, the couple of The Last Dive facing the camera and the last shot of The Two Soldiers, a short from 1979).

“Mónica, Mónica, don’t leave me!”, the ghost added just before the light completely engulfed him.” Is not that light the light of cinema? Watch the beginning of Persona and tell me what you think. Monteiro’s work is as much about the search and praise of the sacred, the Other, as it is as about the vertigo and specular labyrinths of the Self. A door to somewhere else and an infernal circle where the “I” vampirizes everything. Keaton’s theater (The Playhouse) or Levant’s concerto (An American in Paris).

I ask myself if his relation with the Portuguese revolution was not a repetition of Lívio’s story. The second time is always worst and the consequences are often tragic. The metaphysical implications of Lívio’s drama are clear. The absolute other is God, that all absorbing love that filled up his mind and heart. Lost that dream, revealed as self-illusion – “Shit! I’m lucid” – nothing was left except to take the place of the deceased. To play the ultimate parody, the ultimate fraud, God’s comedy:

Jacinta: I only know one called God.

Vuvu: Don’t know him. Can’t recall the name.

Jacinta: He’s a great con man.

Vuvu: With a name like that what did you expect?

(Come and Go, Monteiro with the actress who played his love in The Spousals of God)

|

| Blue eyed, like Monteiro, the cat Silvestre (Hovering Over The Water, 1986) is his most extraordinary alter-ego. In a scene reminiscent of Silvestre (1982), where he watches a girl bath: “Silvestre, my fool, my cat: have you never seen a naked girl washing herself? And if you were a charmed prince? I would blush with shame, hide from you. Do you think I’m beautiful? Is it because the sun tinted my skin with gold? Because my mouth is like a fruit that seems to be always offering itself? I made myself beautiful for your sake and, in the reflexes in your cat’s eyes, I fell happy. Do you know what this is? It’s a black fig that isn’t black but blue and pink inside and from it trickles a honey tear.” Curiously, there is another cat in God’s Comedy, coveting the fishwife’s goods: “Get off, cat! Go and lick your mother’s cunt, get away.” The suggestion seems spontaneous, but considering the context… |

“The lover becomes the thing he loves by virtue of much imagining” (Camões). The problems of self-eroticism and fetishism – even of pygmalionism – are not strange to this universe. The best example might be that of Sílvia/Silvestre. Silvestre was the name chosen for the cat alter-ego watching the girl bath in Hovering Over the Water, like we did in Silvestre. And Silvestre was, after all, a travesty, a being uniting male and female. Suggestive is also the reinvention of Don Jaime’s plays with his dead wife’s clothes in Viridiana: John of God trying the girl’s panties in God’s Comedy.

|

| Watching Silvestre again recalled me of Malick’s creation. And they both like sunflowers... |

And in Conversa Acabada (1990) he plays a producer, João Raposão, John Big Fox, alluding to the trickster of innumerable tales. Big fox presents himself saying that, like Tiresias, he sits and waits for his tits to grow. He makes a phone call about a project to be directed by Fernando Pessoa. His secretary’s name is the feminine form of Fernando, Fernanda, and indeed she has plenty of what the Fox was waiting for. The two will appear in a scene by Pessoa’s statue, in a casting and acting in Pessoa’s film. The photo session by the poet’s statue is perfect to explain how the mirror works. They talk in some sort of infantile imaginary language. She shows him some money, he only takes a note, a reminiscence from past films, alluding to the capital necessary for the project. He insinuates something about her breast. In the end, Raposão, an alter-ego, photographs the statue of Pessoa, the director of the film, another alter-ego (see his moustache), with his feminine alter-ego, Fernanda, in his lap. A ménage-à-trois deign in deed of the poet.

Which wins, the force of life or fetishism? The cunt or Madeleine? But are they really different things in Monteiro? Is not the coiffure of Madeleine a cunt? The Last Dive was part of a series dedicated to the elements. Monteiro chose Water. One of the prostitutes was washing her private (?) parts in the bidet when she finds herself a vanity mirror and asks like Snow White’s step-mother: “Say me little mirror, is there in the world a little cunt more beautiful than mine?”

The strange shot of the mirror in He Goes Long Barefoot... is followed by a hand writing in a notebook, that kind of situation so common in Bresson (Monteiro said Pickpocket, was the pattern/patron of the film) and, even more, in Godard. The second is alluded: “Cinema is a fraud [vigarice] (Godard), but that fraud should can be overcome.” (what follows we will skip) Funny, no? “Can”, not “should”. Can it really? What would be to overcome its fraud? To become both the forger and his victim, like Scottie? But what cinema “forges”, so to speak?

|

| “Who, but Life itself, has the gift of touching Life?” (He Goes Long Barefoot That Waits For Dead Man’s Shoes) To his Eurydice Monteiro dedicated He Goes Long Barefoot…: “To Teresa, this old film of ours”. “Ours” stands for the director or for the director and his love? And what is dedicated to her, the old segment or the entire work? The director is not only watching the remains of his aborted project. He is watching his own life, his own tragedy. And searching for a way out of the dark hells. Monteiro mentioned Maurice Blanchot about this project, who said: “Orpheus’s error seems to lie in the desire which moves him to see and to possess Eurydice, he whose destiny is only to sing of her.” (« L’erreur d’Orphée semble être alors dans le désir qui le porte à voir et à posséder Eurydice, lui dont le seul destin est de la chanter. », The Gaze of Orpheus) Teresa, Eurydice, Daphne is nothing but Life. In God’s Comedy we find another possible dedication to “Teresa”, but of a very different kind. It is the song stimulating the workers of the gelato’s factory. The ones not capable of understanding the lyrics can be spared to the obscenity of the content. |

The last girl addressing Monteiro/Vuvu is called Dafne/Daphne: “I know you. I see you every day coming and going.” She speaks to him from a tree, a beautiful tree of life in the center of the very garden where he, as Lívio, tried a dead man’s shoes some 30 years ago. When he invites her to join him, she answers “I can only give you my shadow.”

Whose shadow? Whose double? Life’s? Is that shadow called cinema? Malick’s Tree of Life? “At, quoniam coniunx mea non potes esse, arbor eris certe” (Ovid).

Poets and artists developed an intense relation with the myth of Daphne and Apollo. Petrarch, most of all, explored it as an economy of desire, both for Laura and the Laurel:

So far astray is my mad desire

in pursuing her who has turned in flight,

and, light and free of the snares of Love,

flies ahead of my slow running,

that the more I call him back,

to the safe path, the least he listens me:

nor does it help to spur him or turn him,

for Love makes him reluctant by nature.

And when he takes the bit forcefully to himself,

I remain in his lordship,

as against my will he carries me off to death;

only to come to the Laurel, where is gathered

bitter fruit; being tasted, others’ wounds, are afflicted

more than comforted.

Sí travïato è ’l folle mi’ desio

a seguitar costei che ’n fuga è volta,

et de’ lacci d’Amor leggiera et sciolta

vola dinanzi al lento correr mio,

che quanto richiamando piú l’envio

per la secura strada, men m’ascolta:

né mi vale spronarlo, o dargli volta,

ch’Amor per sua natura il fa restio.

Et poi che ’l fren per forza a sé raccoglie,

I’ mi rimango in signoria di lui,

che mal mio grado a morte mi trasporta:

sol per venir al lauro onde si coglie

acerbo frutto, che le piaghe altrui,

gustando afflige piú, che non conforta.

Life is an unreasonable, never ending and always condemned to fail run for Laura (or a young cyclist...). The Laurel – the song of Orpheus – is all the poet can aspire. But its fruit does not grant peace to his or others’ wounds. For the contrary.

|

| Vuvu gives birth to the most primitive form of cult image: and if it is nothing but the essence of American cinema/culture? Monteiro is at times really refined. Like when he parodies a famous lyrics from the times of the revolution. When he is eating is chicken soup he changes “They [the capitalists] eat everything and leave nothing” to “He eats everything and leaves nothing”. Nothing, not one thing nor its contrary. |

Who so greatly served life in its altar received a strange retribution. An enormous phallus up the ass, extracted in a scene alluding to the burlesque childbirth of What Shall I Do With This Sword? (the association recalls Paul McCarthy’s Class Fool) This punishment might only partially be assimilated with the director’s cancer or with political commentary (American foreign policy). All indicates that the idea of putting it in that precise place was from the very victim: pas de plaisir sans peine. It was Vuvu who organized that African ritual dance, a fertility rite, like the baptism of Paths. It is always his mirror at work.

Is it a variant of the carnefice e vitima theme? Daphne said: “When you meet your sweetheart, João, don’t forget your whip.” Was not that thing shot from the cannon? It is a kind of missile (and a fetish), one Monteiro associates to the USA (once more the Americans…). He knew for sure Baudelaire’s L’héautontimorouménos:

I shall strike you without anger

And without hate, as a butcher strikes,

As Moses struck the rock!

And from your opened eye,

To water my Sahara,

Shall flow the waters of our suffering.

My desire, swelled with hopefulness,

Upon your salt tears shall swim

Like a vessel which moves to sea,

And in my heart drugged by them

Your dear sobs will sound

Like a drum beating the advance!

Am I not a dissonance

In the divine symphony

Thanks to the hungry Irony

Which shakes me and which tears me?

It is in my voice, screeching!

It is my very blood, black poison!

I am the hateful mirror

Where the Fury scans herself!

I am the wound and the knife!

I am the blow and the cheek!

I am the limbs and the wheel,

And condemned and executioner!

I am the vampire of my heart:

One of the lost forever,

Condemned to eternal laughter

And who can never smile again.

Je te frapperai sans colère

Et sans haine, comme un boucher,

Comme Moïse le rocher !

Et je ferai de ta paupière,

Pour abreuver mon Saharah,

Jaillir les eaux de la souffrance.

Mon désir gonflé d’espérance

Sur tes pleurs salés nagera

Comme un vaisseau qui prend le large,

Et dans mon coeur qu’ils soûleront

Tes chers sanglots retentiront

Comme un tambour qui bat la charge !

Ne suis-je pas un faux accord

Dans la divine symphonie,

Grâce à la vorace Ironie

Qui me secoue et qui me mord ?

Elle est dans ma voix, la criarde !

C’est tout mon sang, ce poison noir !

Je suis le sinistre miroir

Où la mégère se regarde.

Je suis la plaie et le couteau !

Je suis le soufflet et la joue !

Je suis les membres et la roue,

Et la victime et le bourreau !

Je suis de mon coeur le vampire,

- Un de ces grands abandonnés

Au rire éternel condamnés,

Et qui ne peuvent plus sourire !

In this tragic existential background Monteiro’s laughter asks to be heard. How many are willing to live cinema till madness? Who is willing to take this unreasonable game to its last consequences? And who has the courage to follow the poet to his cross? To watch his sacrifice to the end?

One pertinent question concerns the films between What Shall I Do With This Sword? and Recollection Of The Yellow House: do they integrate or not the same narcissist mirror? To say the truth, just to keep with the features, Paths contains already disturbing things making us think in Godard and the oval portrait of Vivre sa vie: Monteiro, as the chief of the bandits (he plays also a friar) who takes away the baby and kills the character played by his own wife: “The bitch wouldn’t get off!” Only afterwards comes the baptism , and by then we are not really sure of what is being baptized. Is the woman alive (flash-back) or dead? Is it the same woman? Was it from Paths that film he would follow the voyage alone with his ghosts?

In Silvestre, it is impossible not to see Monteiro in the pilgrim (or bum?) begging roof and dinner, but with plans to take advantage of the girls with drugged oranges (the orange is important in The Holy Family and The Spousals of God). He was played by the same actor who incarnated his Lívio. When he fails to kill her and is stabbed in front of Sílvia, he expires saying “My poor love.” Was he trying to destroy his mirror? Love and hate for his work? This duo is inseparable in Monteiro. Sílvia says then the sublime words “Now I’m alone with the stars.” Montenegro is given to the pigs to be eaten. The young couple stays together in the room, but when they cross the door she is alone, advancing to the camera, crossing the cosmos. Schubert – the theme of Recollections... – on the soundtrack.

Hovering Over the Water is a more enigmatic object. The English title tries to translate the metaphorical sense of the expression À Flor do Mar (Portuguese title): something that can be felt in/from the sea, something on the eminence of manifesting. But the possible meanings do not end here. The film can be understood as a tribute, a gift. Literally, one possible translation is To the Flower of the Sea. The sea is such an important topus in Monteiro that this work can also be understood as a tribute to the sea. Its spell or flower, the sea as the origin of life, Venus and the territory of childhood dreams. But, as the boat is so central in Hovering Over the Water, it is worth adding the Flor de la Mar was the name of a Portuguese ship that wrecked in Sumatra with an mythic treasure to never be located. An ambivalent title for an ambivalent film. One might think the boat arriving Recollections… is Robert Jordan’s (Laura was searching for the Divine Comedy). Sara tells him never to look back, like he was Orpheus. The cat stays at home – an old fortress by the sea – among the women. Hovering Over the Water is still too secret to risk more than simple thoughts. But in manu Domini sunt omnes finis terrae.

***

“Order is all about that, no? The respect for Death.” (Paths)

|

| Noferatu appearing at the funeral (Come and Go). |

In Snow White, that fascinating masterpiece, after Walser’s photos, the screen becomes black. The dead poet in the snow, the footprints behind (the marks of the shoes), the frozen end of the journey.

The dark is only broken by some shots of blue sky – hurting our eyes now accustomed to the dark – and the desolated view of some ruins. The ruins of the world? With black screen the whole room becomes more visible, the spectators observe themselves. In the end Monteiro appears. If before we had no image, now there is no sound. As if a glass – the glass of a mirror – was between us and the author, an invisible barrier. Apparently close, he dwells somewhere else. He checks his watch, faces us, seems bored. Says “No” (no sound at all) and walks out of the frame. Non, or the Vain Glory of Command… feels like commenting.

|

| “I carry with me at all times the skull of poor Yorick...” (He Goes Long Barefoot That Waits For Dead Man’s Shoes) To laugh or not to laugh, that is the question. |

“No” what? Probably “no” to many things. No to representation. No, this is no ordinary mirror. One side – the director’s, the film – is not a reflection of the other side – ours. And what sees the director?

Monteiro told he thought it was interesting to make a film taking the point of view of the ass’s eye. He even read Quevedo’s Graces and Disgraces of the Eye of the Ass to amuse everyone in the team. This reference is no surprise. The scatological in Monteiro has rare variety and metaphorical richness. In 1974 he wrote that cinema should triturate, digest and shit reality in order to be a transformative power. He stick to the metaphor, as he defecates in Recollections… and The Last Dive (marvelous cameo). In God’s Comedy, of course, he creates a gelato that is de la merde in the words of a famous French critic. And The Hips of J.W. is more about evacuation than inspiration, so he says in the film.

|

| Recollections... and The Last Dive. The solar symbol of the sunflower is associated with the eye of God in the end of The Last Dive. The eye-mirror-sun of Monteiro. “And when I scream I AM THE SUN an integral erection results, because the verb to be is the vehicle of amorous frenzy.” (« Et quand je m’écrie : JE SUIS LE SOLEIL, il en résulte une érection intégrale, car le verbe être est le véhicule de la frénésie amoureuse. », G. Bataille, The Solar Anus, 1924) |

In Snow White, he invites us to consider Bataille, or so it seems:

“The solar annulus is the intact anus of her [the night’s] body at eighteen years to which nothing sufficiently blinding can be compared except the sun, even the anus is the night.”

(“L’anneau solaire est l’anus intact de son corps à dix-huit ans auquel rien d’aussi aveuglant ne peut être comparé à l’exception du soleil, bien que l’anus soit la nuit.”)

The Solar Anus (1924) was already alluded in the idea of the pubic air as Ariadne’s thread, a question almost exhaustively explored by François Bovier and Cédric Fluckiger in their Fétiches et fétichisme, au nom de Dieu (online):

“It is clear that the world is purely parodic, in other words, that each thing seen is the parody of another, or is the same thing in a deceptive form. Ever since sentences started to circulate in brains devoted to reflection, an effort at total identification has been made, because with the aid of a copula each sentence ties one thing to another; all things would be visibly connected if one could discover at a single glance and in its totality the tracings of an Ariadne’s thread leading thought into its own labyrinth.”

(«Il est clair que le monde est purement parodique, c’est-à-dire que chaque chose qu’on regarde est la parodie d’une autre, ou encore la même chose sous une forme décevante. Depuis que les phrases circulent dans les cerveaux occupés à réfléchir, il a été procédé à une identification totale, puisque à l’aide d’un copule chaque phrase relie une chose à l’autre; et tout serait visiblement lié si l’on découvrait d’un seul regard dans sa totalité le tracé laissé par un fil d’Ariane, conduisant la pensée dans son propre labyrinthe. »)

This total erotic frenzy identifying everything – giving a path for energy to escape, a direction to life, not a meaning – seems indeed to conduct John of God’s films. But also Snow White, and maybe more than ever. Monteiro humorously alludes to Snow White in his next and final film, Come and Go:

Vuvu: Now, I’m a widower. I’m in mourning and don’t fuck [deputo].

Fausta: Don’t make me laugh! I believe you had a high old time at the funeral.

Vuvu: What funeral? Don’t make me laugh. My Hortência wasn’t dead, she was sleeping. It was a mortuary imposture put on by the family. Burning with excitement, the fountain of life dripped into the coffin eager for fun and games and naughty wiggles.

Fausta: What! Did you touch her cunt?

Vuvu: Is that a place one should light-heartedly touch? … All I wish for now is a comfortable widowhood worthy of the best waltzes.

Fausta: You must have made hers a black life [vida negra, Portuguese expression for a life with no light, a hell].

Vuvu: Blacker than it already is?

|

| “But you are dead.” (“Ma tu sei morta.”), says Laura to the mirror, in a quotation of the shot from He Goes Long Barefoot That Waits For Dead Man’s Shoes. Above, Monteiro sits in the back, like Buñuel (one of his masters) in Belle de jour (note the Buñuelian insistence of Vuvu in feet) The gelato’s second appearance happens in Hovering Over the Water (À Flor do Mar): “Mother, this gelato isn’t good. It’s nothing but water.” The kid’s comment might be some sort of self-irony about the apparently more chaste register of this oeuvre. In the beginning of the film, while the maid prepares the fish (see the fish in the quotation from Borges of He Goes Long...), she says the cat: “Have no illusions. This one’s not meant for you. Go find yourself a she-cat.” It is different from the rest of the director’s work, yet... we fell something of the spirit of the next films hovering over. |

There is a little play with Rimbaud (quoted in the conversation between father and son, Matinée d’ivresse) in the name of Vuvu’s wife: « trouvez Hortense !» (see H, Illuminations). The answer of the riddle is nothing but Buñuel’s soleil noir... “It is a religious ceremony, in a way... Very touching... Very dear to me.” (Belle de Jour)

“Just now my world has become perfect, midnight is also midday, – Pain is also a joy, a curse is also a blessing, night is also a sun, – go away or you will learn: a wise man is also a fool.”

(“Eben ward meine Welt vollkommen, Mitternacht ist auch Mittag, – Schmerz ist auch eine Lust, Fluch ist auch ein Segen, Nacht ist auch eine Sonne, – geht davon oder ihr lernt: ein Weiser ist auch ein Narr.”, Nietzche)

The (cultural) contraries already identified in He Goes Long…White was also black in that old film. Not only in the repetion of the departure of the train in its negative. In the end of the prologue, the screen goes black for some time to dramatize the (re)birth of the film: “And when he had crossed the bridge, the phantoms came to meet him.” (Nosferatu) The shot rhymes with its negative, Lívio engulfed by the white light. Black and white, darkness and light, the constitutive elements of the film, of the experience of the movie theater.

We end in the theme of necrophilia – or of necrophilia as the ultimate symbol of cinematic fetishism – so explored in this blog. It is worth remembering Monteiro’s praise of Past and Present (1972) when it was released. In the great “necro-film”, which he believed that would have made the delights of Bataille (“Or is it not of that dialectic of "approval of life even in death", so dear to Bataille, that the movie tells us about?”), Monteiro was obviously fascinated by the way auto-erotic specularity married with necrophilia:

“Past and Present is not the reflection of a world; it is a world that mirrors and objectifies itself. The film’s characters are mirrors of themselves (and only of themselves) and with them the use of mirrors loses its usual role of décor to introduce a spectacular dimension that only admits, however, its own show. "There is no doubt that we are here," it is said at the beginning of the film. Here, where? Undoubtedly, in a film.

Systematically built and organized on the notion of the double, Past and Present subtly encloses itself in the game of its duplicity. A play between who sees and who is seen, between showing and hiding, Past and Present is, par excellence, the film of the feast of the gaze. It is therefore the extent and quality of the gaze it produces, which regulates and determines the deepest and most violent movement of the film: the essentially erotic movement. That I remember, and if memory does not betray me, in the history of cinema there is just a film as violently erotic as the film by Manoel de Oliveira. It is (curiously) the most underrated and misunderstood film of Dreyer: Gertrud.

...

Facing a mirror, Noémia looks at her body, in a brief shot … whose beauty is so terrifying and disturbing (to the point of eliminating all the alibis of our good conscience) that even if we spent years inventorying its beauty, we would have said nothing of its beauty.”

|

| The most famous shot of the film is the maid’s eye pepping through Vanda’s room keyhole. A package with a framed object arrives the residence. The husband, Renato, looks curious and nervous to the mysterious package. The maid takes it to Vanda’s room. She orders her to leave. And so she does not resist to peep, and so do we. The package has its back turned to us and Vanda merely lifts the paper to admire the content, so we continue to ignore what it is. She is naked, visibly ecstatic, staging some auto-erotic ritual. Latter we will know that the it contained a portrait of Vanda’s former husband. Someone in the film speaks of the "tendency Vanda has to love the unattainable, whose reverse is the despise for the attainable." |

So this one also had an affair with a dead women? In the light of necrophilia we can think again the motive of the vampire: he is a living dead (all this work is built on the lost/lack of life) who nourishes himself from the living. It was remarked the similitude of Baldung’s imagery with skeleton-like John of God in bed with the princess in The Spousals of God. Necrophilia here might be taken as the lethal love of the vampire as much as the love of the living for dead things (images). As for the last, the analogy between the love of images and necrophilia has been sufficiently treated in this blog. Death is not only the ultimate symbol of sensuality, but of Evil (but are the two different things?). When life turns into frustration men embrace death, or vanity – emptiness, nothingness, bubbles and mirrors (funny as He Goes Long Barefoot... ends among the pines). Cinema as parodic necrophilia is the ultimate degradation one can afford and the best thing to show all despise for the elevated conceptions of Life and Art. Monteiro’s exaltation of the “origin of the world” is nothing but the supreme irony of his cinema. As Luís de Pina wrote about Oliveira’s film, “What to do ... with all this arch-constructed, arch-artificial story, but to take it to the extreme of falsehood itself?” It is the limit of grotesque that Monteiro searched with his John of God.

I suspect it was not in an onanist orgy that Georges Bataille was thinking when he wrote “Eroticism, it may be said, is assenting to life up to the point of death.” (« De l’erotisme, il est possible de dire qu’il est l’approbation de la vie jusque dans la mort ».) The sacred is always an opening to the other, breaking the circle of the self, not expanding it (in no film this expansion is more dramatic than in The Hips of J.W.). But self-parody is important in the French writer. One thing is the sacred described and thought by Bataille, other his experience of it. The tragic and ridiculous is that this opening to the Other is never possible while consciousness – resistance – subsists, and consciousness always subsists in whom is his own God. Until death. Only in death the self dissolves in the universe. The rest is the intolerable but absolute feeling of an aporia always close to a sinister self-parody. We see through a glass darkly but the man fascinated by eroticism wants to see in the flesh. And that, that total identification with the Other, is impossible without a true sacrifice. Monteiro knows his films offer a false sacred, nothing but a fraud, a bourgeois perversion to forget life’s emptiness, or to answer to life’s emptiness with the vertigo of the void. Of the sacred, of life, real life, he could only grasp a shadow, a fetish, a fetish he knows it is such. To that, to his dead wife, he could assent.

***

Monteiro actually turned the cannon towards what was embodied in his earlier work – the dreams of the revolution – so something else could rise out of the past, out of the deeps, his vampire, the ghost of cinema, after all. It was a suicide and rebirth rite built by a vast net of allusions. Of this violence, the audience – our possible dreams – would not be immune. We turn the gun to the camera – from the past or the future – and there we are in front of it.

|

| Spellbound. The camera as a gun is famously explored in Peeping Tom, where all ends with the spectacle of suicide of the very director – to us and himself. Useless to say, he killed prostitutes. |

In 1975 he was an artist in search for the revolution – for the other – and in search for himself. He failed. He lost connection with the outside world an he was infinitely divided in his inner, mirrored world. It is a consensus today that indeed we find floating in this early film much of his latter imagery and obsessions, but to what extent and with what implications 1975’s reality was consumed, vampirezed by a fictional spiral, had never been showed, as much as I know.

As night descended over political reality, as he became once more an ontological and social bum and beggar, 1975’s dreams could be transformed in nothing but shit, a dark parody under the sun of madness. “Tu m’as donné ta boue et j’en ai fait de l’or” (Baudelaire), we learn in school. Maybe the poetic alchemy can work the other way too.

“Pigs rejoice in shit more than pure water.” (Heraclitus, Conversa Acabada, translated from the film) Monteiro felt in the flesh that a paradise was lost, and forever:

“Ah! I promised you a new Greece, and instead you receive only an elegy. Be your own consolation.” (Hyperion oder Der Eremit in Griechenland, The Last Dive)

|

| If we understand the sunflowers as an allusion to the Earth, they might be considered as a tribute to one of the fathers of “cine di poesia”. In the context the allusion sounds strange and rather parodic. Dovsenko’s sunflowers carry mortuary connotations: the death of the hero, the martyr who died for the new society. Monteiro could not be stranger to this ideological ground. In his film it is both the Revolution and revolutionary cinema that are dead. His sacrifice is a sinister parody, his sunflowers are Bataille’s. The poet is alone with his sick sun. |

And all because a girl? In the corridor of Vertigo one dies, other is born.

Samuel (Name of God?) and Esperança (Hope) get together in the end. He wants her to be his girl, as he offers her a manjerico, a present a boy traditionally gives to his girlfriend during Lisbon’s summer celebrations. And they lived happily ever after? Next, curiously, Esperança is writing a goodbye letter. It is the last of Diotima’s letters to Hyperion. As she ends, the camera rises to the tiles with the eye of Providence. Then we are in the sunflowers’ field bathed by the sound of the waves. The couple plays together, crosses the flowers. After we see the flamingos departing (Rilke?) and Cintra, the actor who played Lívio (etc.), answers Diotima, reading a devastatingly beautiful letter from Hölderlin’s epistolary romance. The answer is tragic and changes completely the final mood of the film. By the middle of the answer, the screen is black and Bach enters the soundtrack.

Monteiro makes this shift with absolute genius. Apparently, there is no contradiction at all, because it all makes perfect poetic sense. Something much above logic. Even so, an explanation for the separation of the couple can be encountered.

“I am the father who’s going to give you to eat (comer) my Esperança.” To eat someone is a popular Portuguese expression meaning – brutally, but accurately put – to fuck that person. To fuck Hope is a rather ambiguous proposition. More than to transmit Hope, her father might be offering her to sacrifice. To eat is aggressive, suggests violence, ingestion of the other. The idea is not far from vampirism.

|

| The question imposes: Godard (the good), Malick (the bad), Monteiro (the ugly), are they three sons of the same whore? Is Hitchcock’s Madeleine the common model to these three examples of extreme fetishization? I would not be surprised. Future research about Monteiro will be necessary. |

So, after the night with Samuel, the girl in that room, that room in the end of the long corridor, might not be Hope. She transforms, as she was mute (could not express herself, had no voice) and, after great pain (like in childbirth) in front of the mirror she is able to say “I love you”. Maybe the girl reading the letter is not the one in the sunflowers field, but her double. The sudden apparition of Batallian iconography – structural in the Trilogy of God – is particularly significative. One girl would be Hope, saying goodbye and maybe forever. The other would be John of God’s Ariadne. If so, this is indeed the elegy for the Revolution. The Revolution in Monteiro’s heart. His hope, his hope of seeing Life itself, divine Nature, in the heart of the community, to pick Hölderlin’s terms. The novel is not rarely understood as an allegory of the dilemmas put to the Romantics by the French Revolution (the revolution par excellence), the option between armed fight and promotion of cultural transformation. The director identifies the post-revolutionary direction of his work with Hyperion’s infamous army (do not forget the Revolution ended with a new Cesar/César, Napoleon). Diotima’s words are read in French (the language of the Revolution) and maybe not just because it was the actress’s mother-language. At some point she says:

« … mes plus grandes pensées, telles des flammes, tiennent la glace à distance. »

(“but my nobler thoughts, like flames, hold off the glace”)

Glace is French for ice (ex : la glace est froide), mirror (ex : regarde toi dans la glace) and gelato (ex : elle mange une glace). If in Hölderlin what is at stake is the first, in Monteiro it is necessary to keep in mind all possible meanings. It is the appeal of Life – life as Divine Nature – that holds off the mirror and its labyrinth, the gelato of fetishism. But that Nature is hopelessly lost in The Last Dive. Man only fuses with her in death.

|

| Its scheme is much the same of the Roman funerary portraits, evoking the kingdom of the dead, but more important to think this image (and all other frontal shots by this director) might be Persona. |

But heaven can wait. Suicide was not a way out for Monteiro. Vuvu puts it like this:

“But it’s the problem which is interesting, never the solution. Man, or what is left of him, has to live with the insoluble problem of life.”

I guess Foucault would tell us interesting things about Monteiro’s eye.

***

“In the end, crimes are things that keep repeating themselves.” (He Goes Long Barefoot That Waits For Dead Man’s Shoes)

Has Monteiro’s work something to do with Malick’s Jack?

A good question. There are also two sides in Monteiro. In some films more than others. Or in some parts of the films more than others. Because there are always moments of transparent cruelty, nihilism and extreme fetichization. What is hidden – so to speak – is the pygmalionic side of his work. But if we attached ourselves to his films in a way that would makes us suffer with the end of the illusion, his prompt answer would be: but what reason you had to trust me? To think you knew what these films were?

Monteiro, everybody knew – and he knew everybody did – was the most untrustuble kind of person. Someone who pretended to have dyed so his mother would go to his friends to ask money for the funeral. Someone whose ideal was mens insana in corpore sanum. And being so, one of the directors in the world who established a closer relation with his films, giving his body and soul to the camera. Already in the 70s he wrote “I am the cinema.” We comprehend the claim, but the paraphrase of such a dictum (a sacramental one, by the way) synthesizes perfectly a situation of extreme political ambiguity.

I wonder if the idea of crime, so dear to Malick, is not present in He Goes Long Barefoot That Waits For Dead Man’s Shoes. The Almirals’ widow maid is an allusion to The Green Years (1963), the emblematic film of Novo Cinema (Portuguese new wave, so to speak; Monteiro personally knew the director). Lívio’s refusal to wear Saladas’ old shoes and clothes might suggests that the director was both unwilling to accept the political inheritance of the widow (if she is not an allusion to another film) and the aesthetic(-polithical) inheritance of the maid. The main character of the 1963 film worked in a shoe repair shop…

The maid of The Green Years was killed by her boyfriend. In Monteiro’s film, the maid is seduced by Mário (obviously another double) and they both enter the apartment. Is not death insinuated in that scene? Is not the director saying this is some sort of crime? What was Monteiro bringing to the Portuguese cinema? Saladas’ clothes are sold in the pawnshop, the friends divide the money (see how Lívio and John of God divide the money in Recollection…) and then begins the third part of the film, with Lívio and Mónica. The money was to invite Mónica to dinner. It all suggests that the money was in fact to make the very film, to meet the girl in the mirror.

But concentrating in the more obvious similarities with the idea of Jack. It would be necessary to explore the director’s relation with Pickpocket. If Bresson’s film was indeed the pattern and the patron of He Goes Long Barefoot… it is impossible not to grant a serious thought to the question. Monteiro’s life had similarities with Michel’s. He was very poor, living in a rented room with his mother, I believe. He spent his days in coffeehouses and bumming around. He felt imprisoned in his life. It is not impossible that he saw his films as a crime, a crime-game in which he could take the lead and set things straight with the world.

It is true, jokes with the ignorance of the spectator do exist. There are plenty and now everyone will be able to find them. And there is Snow White.

|

| Former shot: “Errata: In the Prince’s line, where its heard “humanity” [humanidade], it should be heard “humidity” [humidade].” Above: “Though it is a very human humidity, the director takes the opurtunity to ask his apolodgies to the spectator, here and now transformed into spectacle. João César Monteiro” |

Obviously, the relation with such oeuvre was complex from the beginning. What Shall I Do With This Sword? was certainly not cinema of the people for the people... nor to some intellectuals. It did not comfort, fragile and ridicule aspects of the revolution were explored with irony, it was plenty of hermetic references and ambiguous symbols. It was distant, analytical. Personal and ludic. The attacks started right away, inspiring Monteiro’s virulent answers.

Democracy brought him freedom and money to make films. But as the funds were in great measure public the voice of the audience as tax-payer started to be heard. The public voice, the voice of the public. What includes a considerable part of critics to whom his films were ridiculous, incomprehensible, obscene, preposterous and pretentious to the limit. To some, just a big laugh at our expense. He was only after the aura of the solitary genius. Monteiro did not waist the opportunity to show all his despise. When bullied by reporters about the Portuguese public’s reaction to Snow White, the answer was: “I want the Portuguese public to go fuck itself.”

Having in mind the previous statment by Monteiro that a film made by him “for the public” would be a “pornographic and spectacular film” one thinks, among others, in Debord, the director not only of The Society of Spectacle but also of films like Hurlements en faveur de Sade and In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni (“We go round and round in the night and are consumed by fire”), a film with a specular title, a palindrome, a film where we read at some point: “Here the spectators, having been deprived of everything, will even be deprived of images” (“Ici les spectateurs, privés de tout, seront encore privés d'images”) And a film opening with the famous statment: “I will make no concessions to the public in this film. Several excelent reasons justify, in my eyes, this conduct; and I am going to state them. First of all, it is well notorious that nowhere have I made concessions to the dominant ideas of my era or to any of the existing powers. Moreover, no matter the era, nothing of importance has ever been communicated by being gentle with a public, not even one composed by contemporaries of Pericles; and in the frozen mirror of the screen the spectators are not looking at anything that might evoke the respectable citizens of a democracy. Here is the essential: this public, so totally deprived of freedom and which has tolerated [just about] everything, deserves less than any other to be treated gently.” (“Je ne ferai dans ce film aucune concession au public. Plusieurs excellentes raisons justifient, à mes yeux, une telle conduite ; et je vais les dire. Tout d’abord, il est assez notoire que je n’ai nulle part fait de concessions aux idées dominantes de mon époque, ni à aucun des pouvoirs existants. Par ailleurs, quelle que soit l’époque, rien d’important ne s’est communiqué en ménageant un public, fût-il composé des contemporains de Périclès ; et, dans le miroir glacé de l’écran, les spectateurs ne voient présentement rien qui évoque les citoyens respectables d’une démocratie. Voilà bien l’essentiel : ce public si parfaitement privé de liberté, et qui a tout supporté, mérite moins que tout autre d’être ménagé.”) Debord and Malick... Tempting exercice but lets skip it.

So, in Snow White the announcement that the “spectator had been converted into spectacle” is not necessarily to be understood in a positive way. Like, for example, that the spectator became his own spectacle, as he was confronted with the inherent subjectivity of seeing. Indeed, the spectator – as that hateful entity confronting the mirror and demanding to be represented, reality – is absorbed, vampirezed, triturated, digested and expelled – so the director can make his gelati, produce his soleil noir.

|

| One of the possible readings of the shot is that everything is aspired to the black of the pupil. A vampire-eye... (For this final eye, see this article by Francesco Giarrusso as an introduction; and do not forget Vertigo) |

In the beginning of He Goes Long..., we shared the director’s point of view. In the end, director and spectator confront each other. First we are spectators, after the director’s spectacle. There is provocation. Or just hope? If there is vampirism, it is mostly self-vampirism. Monteiro is above all his own spectacle.

Anyway, about the answer to the TV Monteiro should be absolved. Or at least there are attenuating circumstances. Because nothing is so disrespectful to an audience as to give it something to its supposed image and likeness. Comforting tales. Soap-operish escapism. Sovereign art asks for a sovereign spectator (lacking a better word), not for a public. Public? “Public are the urinals.” (M. de Oliveira) A “public” might just deserve to be used as one, what is more or less what happens in Le bassin de J. W.

***

The acquaintance with Monteiro’s universe (and with one of his masters, Godard) had a decisive importance in the genesis of The Imaginary Family of Terrence Malick. Now it was Malick who invited me to go back to Monteiro to reevaluate one or two things in his work.

I heard Lívio’s voice: Stop! Give them work. Although aware of its limitations, I decided to stop editing this review. Contradictions, under-explanations, over-explanations, lacks and so on are to be taken as an encouragement to perfect this image of Monteiro’s work, if the reader sympathizes with it at all, this is. To offer a revision of all Monteiro’s films under this new light would take too long. As his beloved Joyce said about Ulysses:

“I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.”

*

“To be frank, I haven’t minimally thought about it, but as it is so …, I can only manifest my gratitude with that modesty so typical of mine and say: ‘Thank you my people!’”

(Monteiro when asked what he thought of the recent critical interest for his work in 1998)